http://www.afropop.org/wp/4472/afro-dominicana-the-other-dominican-republic/

Afro-Dominicana: The Other Dominican Republic

We bring some much needed-attention to Afro-Dominican music, some of the richest and least-known sounds coming from the Caribbean. The Dominican Republic is best known for merengue and bachata, two essential parts of the mainstream Latin music landscape. Both styles have heavy African influences, but aren't considered "Afro-Dominican" music – that term is reserved for the 60 some-odd traditional rhythms found on the island, deeply-African sounds that make the complex grooves of salsa or merengue look like beginner's stuff. There is an astounding musical diversity. Whole music traditions can change from one town to the next, each with its own choir of unique instruments.

Although there are secular styles as well, most Afro-Dominican music is deeply integrated with Afro-Dominican religion, syncretic practices that fuse the Catholic saints to African deities, much like Cuban santeria or Haitian vodou. From energetic Saint's Day parties to private ceremonies to mass pilgrimages, Afro-syncretic spiritual activities play a major part in the lives of many Dominicans, and music is always there at the center, providing an ecstatic, transcendent, communal way of interacting with the divine.

Afro Dominican music is a well-kept secret thanks to a long and complicated relationship between Dominicans and their strong African heritage, further nuanced by the 31-year dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, who actively persecuted the country's African cultural manifestations in an obsessive quest to Europeanize the country. Even though Afro-Dominican music is played every day, it is rarely discussed in public – it's almost a taboo.

Nevertheless, the traditions are strong – this is living, breathing folklore. Whereas in some countries, traditional music is dead except for nostalgic recreations by folkloric ensembles, this music is thriving with virtually no support of any kind.

Below, you'll find a brief guide to Afro-Dominican music styles – by no means a complete list. Take a second to follow the links and see the traditions being practiced for yourself. Also, don't forget to scroll to the bottom for links and information on the Afro-Dominican fusion artists featured on our radio program.

Salve

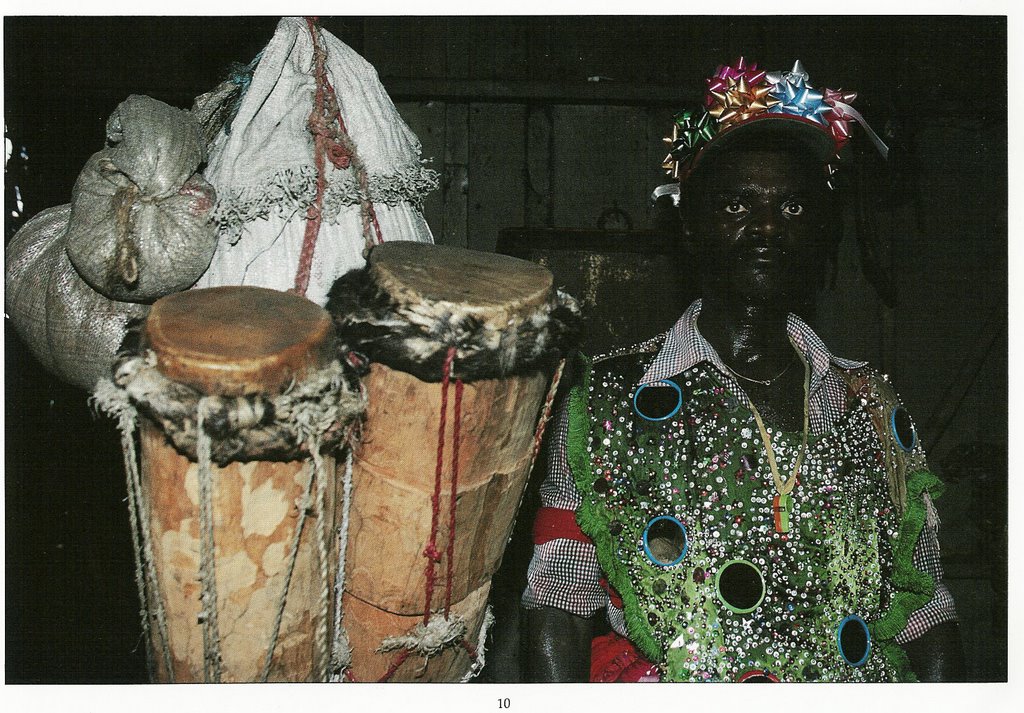

Palos and salve are the most common styles of Afro-Dominican music. In fact, some ethnomusicologists say that palos should be the true Dominican national music, rather than merengue, since it's found in some form virtually everywhere on the island. Palos, which means "sticks", gets it's name from the trio of tall, skinny drums it is played on. The drummers are accompanied by the omnipresent Dominican guira or metal scraper, and singers who venerate the Catholic saints and their sycretized African counterparts with call-and-response style melodies and improvised verses.

The music is an essential part of Afro-Dominican spiritual life. Popular religious celebrations are often referred to as fiesta de palo, or palos party, after the dominant role of the drum. Ceremonies usually occur on the Saint's Days of the Catholic devotional calendar. For example, October 20th is Santa Marta's day, so her devotees might arrange an party in her honor. In towns or neighborhoods where she is the patron saint, there will likely be a novena, in which festivities occur for nine straight nights, culminating in a all-night party on the actual Saint's Day. In either case, an altar will be made and palos drummers will play, often for hours and hours on end. As the music intensifies, worshipers may undergo possession, in which the deity descends to the Earth to give advice, relay messages from deceased relatives, or sometimes just to have fun. Once the possession stops, the person often has little or no recollection of what just happened.

Image from LAMECA archive

These may be religious events, but they aren't staid affairs in any sense – people drink, dance, sing, and have a good time, and its all about bringing the community together. While most palo songs are about the virtues and exploits of the saints and gods, many are just festive songs with secular topics.

Salve is a related genre that is played in a lot of the same contexts, but with different instruments and rhythms. The name comes from the Salve Regina, a catholic psalm, and many still sing a sacred, acapella salve that preserves the medieval modes of old Spanish hymns. The ecstatic salve played at religious parties however, is all about percussion – featuring large numbers of tambourines playing interlocking rhythms and a melodic drum called the balsie, whose player alters the pitch by applying pressure with his foot.

Salve may be played in fewer parts of the country but it's one of the best-known sounds, largely because it's the sound of choice in Villa Mella, a poor suburb of the capital often thought of as the epicenter of Afro-Dominican traditions. The salve group of Enerolisa Nuñez, from Villa Mella, is one of the most widely listened to – thanks to her inclusion in merengue-star Kinito Mendez's salve-merengue fusion album A Palo Limpio as well as an excellent recording of her group by the Bayahonda Cultural Foundation.

Congos

Congos is a unique musical phenomenon that has intrigued anthropologists both at home and abroad for decades. It's played by a group called the Cofradia de Los Congos del Espiritu Santo de Villa Mella, a religious brotherhood based in Villa Mella and the guardians of a musical tradition that dates back several centuries. The cofradia is thought to be directly descended from the religious-fraternal organizations of enslaved Africans during the Colonial Period. Africans from similar cultural regions on the continent often bonded together in these societies, and the music of the Congos is thought to be rooted in styles from Central Africa.

The group is organized into a hierarchy, with a king, a captain and other titles, and membership is passed down the generations. Their responsibility is to maintain and pass on a cannon of 21 songs, played on a unique set of self-made shakers, claves and drums. The music is most often played for the funeral rites of Cofradia members, helping the passage of their souls to the next world. After death, congos music is played for a nine-night novena, and the ceremony is repeated a year later and then again two years after that. The ritual displays a strong linkage to African ways of dealing with life and death.

The congos were recognized by UNESCO in 2001, raising the group's national profile in a country hesitant to support Afro-Dominican culture. When long-standing Congos leader Captain Sixto Minier passed away in 2008, there was an impressive outpouring of affection. Still, the government has been criticized for not doing enough to support the group, and the congos continue to struggle in the difficult material conditions they've faced for centuries.

Gagá

One of the most popular sounds for Afro-Dominican revivalists, gagá is the music of the bateyes, the sugar-cane cutting camps where Haitians and Dominicans live and work side-by-side. Gagá is rooted in Haitian rara, a kind of street music played in parades during the Lenten season. It's music for the forest spirits – for the renewal and rebirth found in nature, echoing Christian Easter themes of resurrection. The breakneck-paced music is played on drums and percussion, but also with a series of one-note homemade trumpets made out of wood and metal. The trumpets interlock to create haunting melodies in an effect known called hocketting.

Haitians suffer heavy discrimination in the Dominican Republic, thanks to a long history of anti-Haitian indoctrination from Dominican elites. Many Haitians illegally reside in the much more prosperous D.R. and are frequent victims of abuse by employers and police. Haiti is a major factor in the racial complexities of Dominican society. After rebelling against the French and declaring independence in 1804, Haiti conquered the Spanish half of the island. Dominicans won their independence from Haiti, not Spain, and have long constructed their identities in opposition to an African, Haitian "other."

Picture by Justin Mercer

Despite widely held prejudices, the two countries have a lot in common and have traded culture back and forth across the years. For example, Haitian pop music style compa was inspired by golden-age Dominican merengue, and the Creole names for Afro-Dominican deities betrays roots in Haitian spiritual practices.

Gagá, while having undeniable Haitian roots, has steadily developed its own sound in the Dominican Republic, becoming a part of the Dominican cultural landscape. It's performed primarily during Semana Santa.

Guloya

For most of its history, sugar cultivation was the bedrock of the Dominican economy. In the late 18th century, migrants from English-speaking Caribbean islands came to the Dominican Republic to fill a demand for labor in the cane fields, settling in southeastern city of San Pedro de Macoris. The Dominicans called them the cocolos, thought to be a mispronunciation of "Tortuga", a nearby island from which many of the migrants originated. The cocolos brought with them the mores of the Anglo-Caribbean. Their talent for cricket was easily adapted to baseball, leading San Pedro to be nicknamed "the city of shortstops" for the incredible numbers of Major-leaguers to emerge from the city.

The cocolos also brought their music traditions, referred to commonly as guloya. It's an Afro-Caribbean adaptation of English Christmas pageants. The momises, as these mummers as called, retell biblical stories such as the battle between David and Goliath, mock-fighting in fabulously-colored costumes. The music is a take on English fife-and-drum music, played on triangle, snare drum, and homemade flutes. It takes on a rollicking, almost New-Orleans style feel in the hands of the cocolos.

Mumming-influenced traditions can be found across the Caribbean in places where the English left their mark. A popular masquerade, known as John Canoe, is practiced in the Bahamas, Jamaica, and even by the Garifuna people in Central America. In the Dominican Republic, guloya continues to be performed every Christmas season, though as the older generations die off, there is a danger of the tradition gradually eroding. Younger generations are more culturally Dominican, speaking Spanish as a first language instead of English.

Sarandunga

The diversity of living folkloric music traditions in the Dominican Republic is staggering, and one perfect example is the sarandunga. The sarandunga is played exclusively in Baní, a small city in the country's South, a region with a particularly strong Afro-Dominican presence. What's more, the sarandunga is played only on one event of the year, the festival of San Juan Bautista, or John the Baptist. The tradition is maintained by a local cofradia, not unlike that of the congos, and continues to be maintained without help from folklorists or anyone else. Sarandunga is played on its own set of 3 small drums, and contains three movements, the morana, the jacana, and the bomba, each with a distinct rhythm, melody, and lyrics.

La Comarca

Olivorio Mateo, better known as Liborio, was a messianic figure and leader of the Liborista religious movement that arose in the early 20th century. He performed miraculous healings, drawing a large following in the remote Cordillera Central, where many communities descend from cimarrones, slaves who escaped from the sugar plantations and found freedom in the mountains. In the 1920s, American occupying forces hunted down and killed Liborio, deeming his movement a threat. Today, he is a sort of folk hero. The music he used for healings, the comarca, lives on in the deep interior of the country. Played on accordion, it bears resemblance to the many folk dance genres found in the country, but also has a religious/magical connotation.

Bambula

The bambula is yet another Afro-Dominican style with fascinating historical roots. It comes from the beautiful Samana peninsula on the island's North-East, famous for migratory whale populations and off-the-beaten track beach towns. Samana is home to a group known locally as los Americanos. They are descendents of black American Garveyites, who followed the pan-Africanist teachings of Jamiacan-born activist Marcus Garvey. Garvey raised money to build a fleet – the Black Star Line – with the purpose of eventually re-patriating African-Americans to the African continent.

The group in Samana arrived in the 1800s to become a part of the new Haiti, the world's first post-colonial black-led nation and at one time the rulers of the entire island. Their music, the bambula, has roots in French-Caribbean music, but is also traced back to early African-American music coming out of New Orleans. Today, the bambula is infrequently played, though there is an initiative in development—the Bayahonda Cultural Foundation— to help rescue the tradition and encourage sustainable cultural-tourism in the Samana peninsula.

Afro-Dominican Fusion Music

Over the years, many alternative artists have drawn on Afro-Dominican music in their work, finding inspiration and power in the same African heritage so vehemently opposed by mainstream Dominican society. The first such group of note was Convite, formed in 1974 by young intellectuals at the Autonomous University of Santo Domingo who went out into the countryside to learn about this music, bring it back and fuse it with acoustic instruments and rock and roll aesthetics. Convite eventually broke up, but its members went on to be foundational figures in folklore studies and anthropology in the country.

Today, there is a new movement stirring, a new generation of Dominicans partially removed from racial attitudes of their parents. While it is still a fringe subculture, more and more Dominicans are embracing African roots and a crop of young bands are mixing Afro-Dominican folklore with reggae, rock and jazz, among other styles.

Below are some links to some of the fusion musicians featured in our program:

La Guardia Vieja – Those who led the way.

The New Generation – New sounds, new voices.

No comments:

Post a Comment